This one’s going to be a more in depth review than I usually do, so please be aware SPOILERS abound.

First, the caveats. I am a northerner who was raised in the South. I grew up in both the New South and the Old South. I am white, my best friend since the 4th grade – some 22 years now, is black. I have a degree in history, I earned a graduate degree in Museum Education, I work at a historic site in the Northeast and I deal with how to interpret the history and consequences of slavery and indentureship as part of my job. I will take part in shouting matches with people who claim lynchings only happened in the South, or a long time ago (it continued in the United States until the 1960s). For these reasons much of what others most likely found difficult to read or shocking, to me, is just par for the course. Jen K and I had virtually the same response to the book.

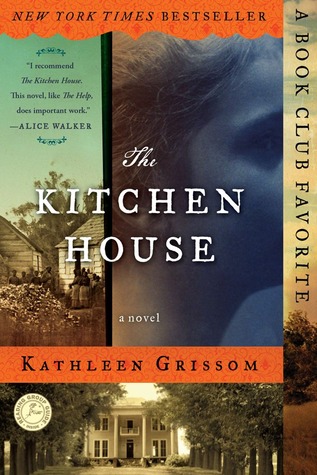

That said The Kitchen House opens up with one of the protagonists discovering someone she cared for lynched. What Kathleen Grissom does well in this book is to present the truth of the times she is describing (1790-1810) or the setting of her story (Virginia) accurately. Grissom did her research. She studied slave narratives, interviewed slave descendents; she visited and researched at the Virginia Historical Society, the Black History Museum, and Colonial Williamsburg. If only all historical fiction writers did the same. The problem was not in the research, the problem was in Grissom’s distaste for what she knew and what she found.

Slavery is quite simply one of the great national tragedies of the United States. There is no getting around that. It is virtually impossible not to have a gut reaction to the way in which other humans were treated for hundreds of years in this country (not to mention around the world). The physical, psychological and economic toll is still being felt, and will take much more time and much greater minds than mine or Ms. Grissom’s to come to terms with. But, the suffering that is unfortunately essential in the story of The Kitchen House means that the author must leave her emotions at the door. By not being able to fully put aside her own appalled and disgusted reactions (Grissom’s own descriptions of her reaction in her Author’s note) and simply tell the story, Grissom hamstringed one of her two protagonists and perhaps ruined the final third of her novel.

At its root The Kitchen House is the story of two women: Lavinia and Belle. Lavinia and Belle alternate in narrating chapters of the book, giving us insight into the two different angles of the story. Lavinia arrives at Tall Oaks as a very sickly six year old Irish orphan who is indentured to the farm. Being white, young, and sickly she is sent to live in the Kitchen House with Belle. Belle is the illegitimate daughter of the owner of Tall Oaks, Captain James Pyke. Captain Pyke fathered Belle before his marriage and she was raised until that time by his mother in the Big House. After her grandmother dies and the Captain marries, Belle was sent down to run the Kitchen House under the supervised care of Mama Mae. Mama Mae and her husband Papa George take Belle, and later Lavinia, into their family of House Slaves and the reader follows along with the various threads of storyline which are woven through the complex relationships of everyone living at Tall Oaks.

For the first half of the novel the reader becomes acquainted with the running of a plantation, although we are kept out of the Field Workers lives. Lavinia’s story drives the narrative. Her chapters eat up ten times as much real estate as Belle’s. This is a hindrance to the storytelling while at the same time it speaks greatly to the character development. Lavinia is a dreamer and remains childlike even while being continually exposed to the darker aspects of life. She never completely pieces together the things she sees and experiences, although the reader cannot help but to. I blame this wholeheartedly on Grissom’s own reaction to the atrocities in the narrative (beatings, rape, incest) and as an author she is protecting the character from fully realizing what she is experiencing and in the long run that means that Lavinia moves forward with such naïveté that she nearly brings everyone’s lives to an end.

The counterpoint to Lavinia’s viewpoint is the no nonsense approach Belle brings to bear. Belle is the more complex character with the more detailed personal history. She is the child of the captain and is promised her free papers. She continually refuses them because she does not want to leave her family or the man she loves. She is raped by her half brother Marshall and finds herself pregnant with his child. She waits too long to ask Captain Pyke for her freedom, after his wife Martha hides Belle’s free papers, and he dies before he can grant freedom for herself and her son. She lives in fear of the day her half brother inherits Tall Oaks and is continually planning her escape, all the while entering into a relationship with a married man. Belle is separated from Lavinia for the second half of the novel and no longer able to balance out her gullibility with her own true understanding of how the world works based on her own experiences.

The second half of the novel finds Lavinia living in Williamsburg with the sister of Martha Pyke once Martha is committed to the Hospital for the Insane. This is where Lavinia’s story begins to unravel, and perhaps her greatest character flaw is revealed. Lavinia will not ask a question. She doesn’t ask about details she doesn’t know about her loved ones or about her own future. Ever. Much of the plot movements in the second half of the novel revolve around Lavinia making decisions about her future without asking anyone with the knowledge to tell her what her options are. Admittedly her options are few coming of age in the first decade of the 1800s, but there were still options available to her. However, because she doesn’t want to offend the Maddens, or reveal that she doesn’t know the terms of her indenture, she careens from poor choice to poor choice. It culminates in her decision to marry Marshall Pyke. Yes, that Marshall Pyke.

Because Grissom kept Lavinia from piecing together the details of life at Tall Oaks she makes the grave error of trusting him and marrying him. If she had not trusted him she could have found herself married to the quite lovely Will Stephens. The most frustrating part to me was that Grissom could have explored the decay of Marshall Pyke without having him marry Lavinia. She did not need to endure his physical violence and subsequently turn into a laudanum abuser as Martha Pyke already had. The lynching we see in the first chapter, which is where we know we are going to find ourselves again at the end of the novel, could have been reached in another way. Instead, because Lavinia is too naïve and weak to choose otherwise the final hundred pages of the book read as a litany of sin and destruction.

It is for all these reasons that I had a hard time deciding on a rating for this novel. I’m going with three because it is well researched and written, even if plot choices and character development left me shaking my head in disappointment of what could have been.