Banning books works.

Unfortunately.

On a number of levels.

It keeps books out of the hands of the people immediately effected by the ban.

It emboldens the challengers to go after more. To look beyond the books themselves to take further action against the represented groups.

I would like to say that the benefits of exposure to the challenged titles outweighs the damage, but I can’t. Because media attention is short-lived and successful challenges can lead to bans that left unchecked can keep those books off publicly accessible shelves for years or decades.

It is a tool of power. Power and control. In both the short and long term.

Worse yet, the ban doesn’t even have to hold, or exist for long. Merely being challenged will often pull a book out of circulation due to fear of dealing with the fallout of shelving these ‘bad’ books. Libraries in the United States are, by and large, publicly funded institutions which means that the money that puts books on shelves at all can come under fire if public opinion isn’t good. Quietly across the country boards and directors are making the choice to pre-emptively pull books off shelves, effectively silencing the authors and leaving the readers who need these books out in the cold.

A lot of the rhetoric flying around right now (February 2022) is full of people with good intentions doing feel good actions that provide no real redress to the actual problem. And that’s shitty, because they are acting in selfish ways instead of in selfless action. And as usual, its people who look like me doing the shitty thing on both sides.

I read banned books as a student, not because I knew to look for them, or that they were available to me, but because I had adults putting those options in front of me, occasionally at their own peril, and parents who were supportive of my reading and education broadly.

I read banned and challenged books as an adult because the idea that someone feels they have the right to decide what is acceptable to read, makes my skin crawl.

Some of the most beautiful reading experiences I have had are with banned books… because often banned and challenged books are telling deeply personal stories of the vagaries of this life that we are given. The idea that anyone ‘needs to be protected’ from truth is so rage inducing that I often cannot put it into words, even while actively seeking to read and review banned and challenged books all the time, even while planning to lead a book club about banned books this September.

Because why are books being banned or challenged right now?

Ostensibly the major complaints come down to whether a book is appropriate for its audience. Your mileage may vary on that on its face value. What it is really being used for is to keep books that don’t fit into someone’s view of what “children” or better yet “their children” should be exposed to. Because we don’t talk about those things.

Things like racism or racial conflict.

Or war.

Or genocide.

Or violence.

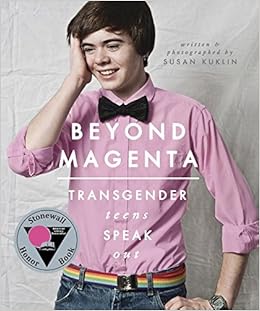

Or gender identity.

Or queer love.

Or what constitutes blasphemy.

But the world has all these things. Some in greater proportion to others, but they are all true.

And objective truth is more important than comfort, is more important than the propagandist forces that would tell you to be afraid of it. That are after accumulating power based on what they can make you afraid of, of whom they can paint as the villain making your life worse.

Because the thing to fear is living in the dark. Of not knowing truth and believing lies. Of creating boogeymen where none exist.

Because lies are the tools of the oppressors.

And people are just people, beautiful and complex, and fascinating.

Fight back. Don’t be afraid.